After the first Damien there were several iterations, larger boats most with steel hulls.

cf. Northanger

courtesy Gérard Janichon

By Creed O'Hanlon

In May, 1969, a small sloop named Damien slipped its mooring within the French harbour of La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast of south-west France, and made its way seaward through the 12th century fortified stone walls that protect its entrance. Once across the narrow channel between the harbour and the low shores of Ile De Ré, it altered course northwest, out into the wide maw of the Bay of Biscay. She wouldn't be seen again off this coast for another four years.

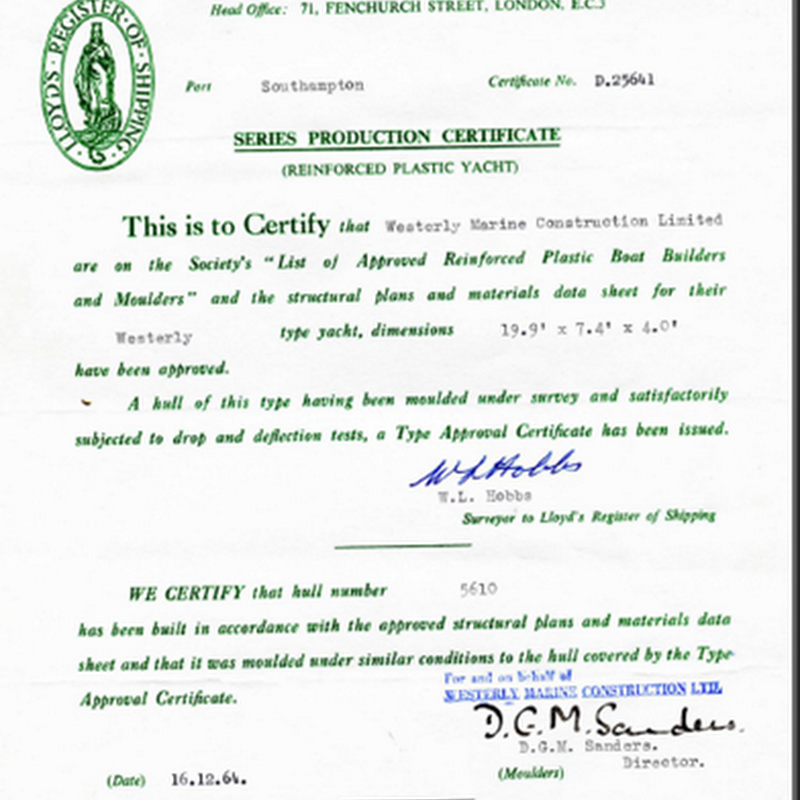

The beginning of this voyage was the culmination of a long-held dream for two young Frenchmen. Five years earlier, when they were both still teenagers, Jérome Poncet and Gérard Janichon seized on the idea to build the 33-foot, cold-moulded, reverse-chine Robert Tucker design and follow in the wake of their hero, Bernard Moitessier.

They ended up sailing to places even the far-voyaging Moitessier had never ventured.

After rounding Ushant, the westernmost extremity of France, they made their way 'up' the English Channel to the North Sea and after a layover in Bergen, in Norway, continued north to Spitzbergen, in the Svalbard Archipelago, well inside the Arctic Circle. They then turned south-west to Reykjavik in Iceland. From there, they laid a course past Greenland's Cape Farewell to the east coast of the USA. After rounding Cape Hatteras and beating south to the Caribbean, they port-hopped to the north-eastern coast of Brazil, where they decided to sail 2,000 nautical miles up the Amazon before resuming their voyage south. Months later, after rounding Cape Horn from east to west, they double-backed and sailed homewards through the Southern Ocean, via the three great Capes (including a second rounding of the Horn). They eventually logged more than 55,000 nautical miles over a track that spanned the parallels of 80ºN and 68ºS and encircled the globe.

Janichon and Poncet were among the most prominent of a distinctly Sixties' generation of young French sailors who were all inspired not by phlegmatic English deep-water sailors, such as Francis Chichester, Alec Rose, Blondie Hasler, Bill Tilman, Robin Knox-Johnston and others, but by the somewhat hermitic, hippy-ish Bernard Moitessier and his 'agricultural', Jean Knocker-designed, 39-foot steel ketch, Joshua. Born and raised in colonial Vietnam, Moitessier was a tough, highly skilled sailor – arguably, the most accomplished of his age – but he was also a man very much of that odd, spacey time: a dope-smoking, philosophical, manic-depressive visionary for whom ocean voyaging was as much an opportunity for Zen-like self-exploration as it was an adventure.

Damien's long, extraordinary voyage attracted little attention outside of Europe and Janichon's classic book, Du Spitsberg Au Cap Horn (From Spitzberg To Cape Horn) was published only in France (one of many wonderful maritime titles assembled by the local house, Arthaud). The influence of Moitessier's reflective interior monologues are occasionally apparent not only in Janichon's writing but also the narration for the 16mm film Poncet and he shot during their voyage (just as Moitessier did on his non-stop voyage around the world during the Sunday Times' Golden Globe Race in 1969). An excerpt from Janichon's film, during which Poncet and he recklessly pilot Damien right up to the sheer blue cliffs of a towering, castellated iceberg in the high latitiudes of the Southern Ocean, can be found here: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x9t2bt_retour-sur-le-voyage-de-damien_travel

In these days of corporate sponsorships, professional crews, and exotic multi-million dollar vessels built to claim the most arcane of ocean passage records, its worth reminding ourselves that the men and women who undertake such unsung, unsponsored, under-funded but perilous voyages in small, spartan yachts for no other reason than the voyage itself – think Roger Taylor in Ming Ming or the Berque twins, Emmanuel and Maximilien, in their tiny, home-built Micromegas – still have more capacity to capture our increasingly meagre imaginations than the flashiest, fastest, highest profile, round-the-world racer.